In the previous post, I described how thermal power plants use a massive amount of water. This time we are going to explore a specific case. As usual, it's China.

Power plant water use can be a problem in a water-stricken area. Let's look at a case-study. China is a water-stricken area, and has a lot of thermal power plants. In fact, China uses more primary energy than any other country in the world. Unfortunately, their power plants are far less efficient than they should be. So they are wasting water, and this is unsustainable. Moreover, China has 1,350 million people. The US has 314 million.

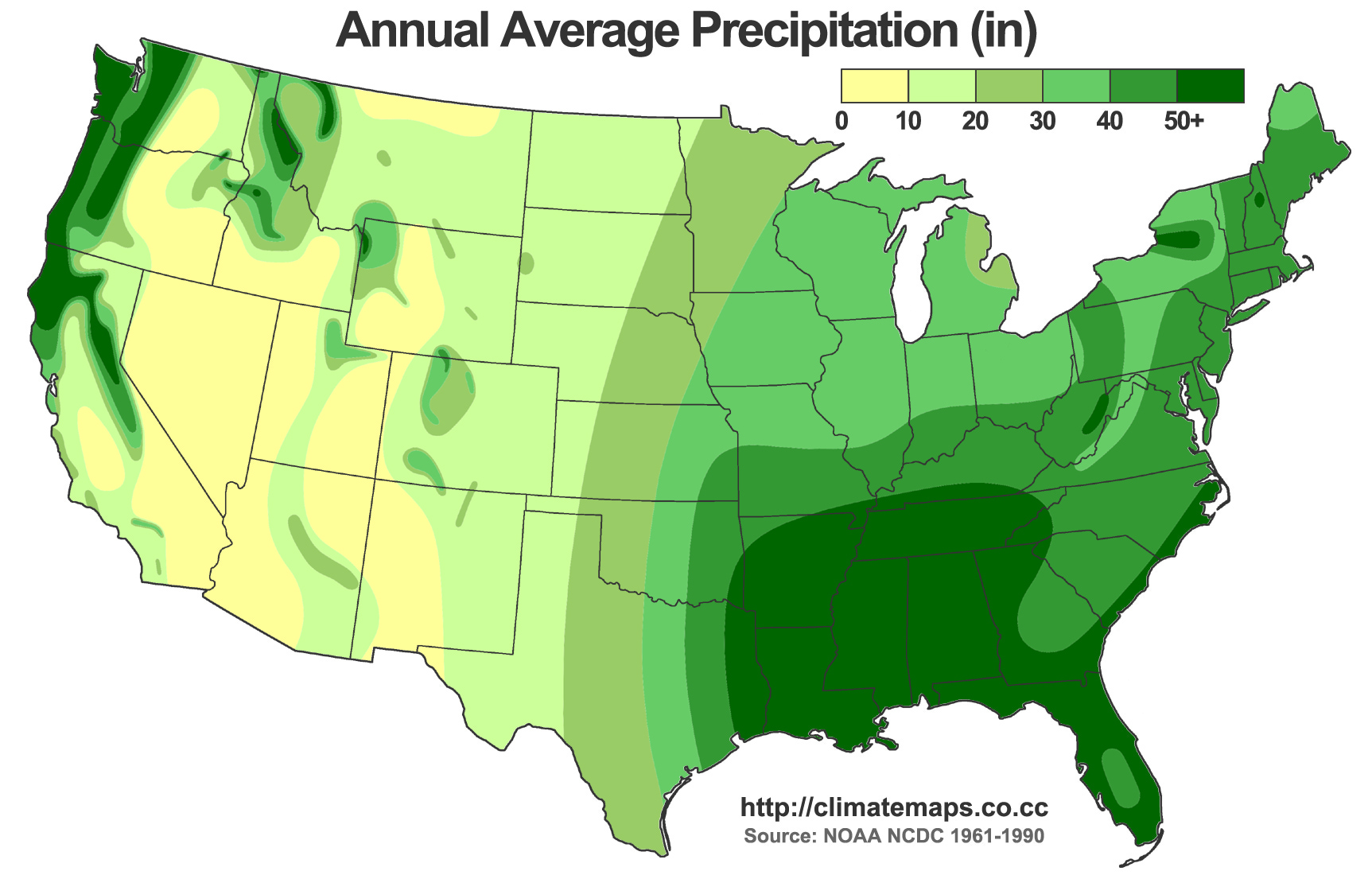

First, let's look at the rainfall of China, compared to the US:

Looks pretty similar, right? Now recall that the US has 1/4 the population of China. And pretty much the exact same amount of area. Keep that in mind while we look at China's powerplant locations:

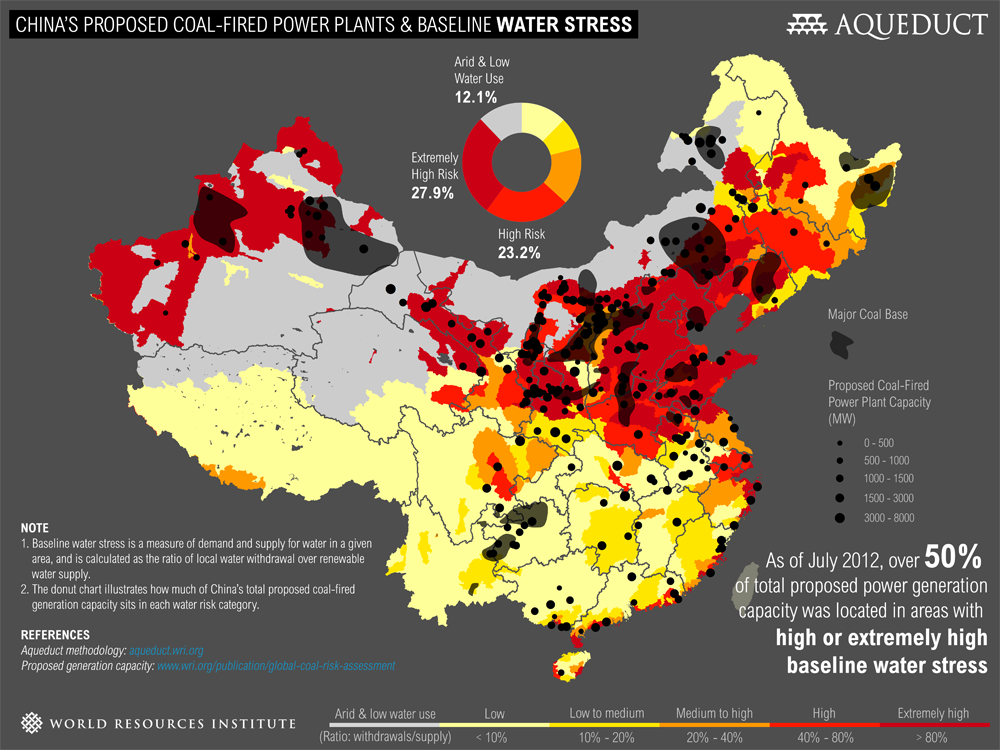

China's water stressed areas, compared to where power plants are planned. Source,

So. The places that have the most people and need the most power are the same as the dry places. In other words, China is building the bulk of its thermal power plants in the area that can't provide sufficient water to cool the power plants.

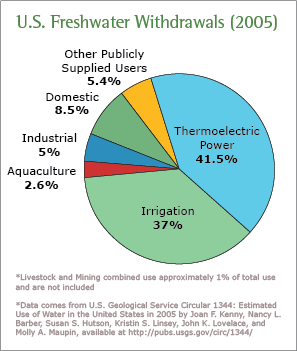

Before coming to the complete picture, let's check out the water use:

Fresh Water Use in the US.

source

In the US, 80% of water use is to grow food and to make electricity.

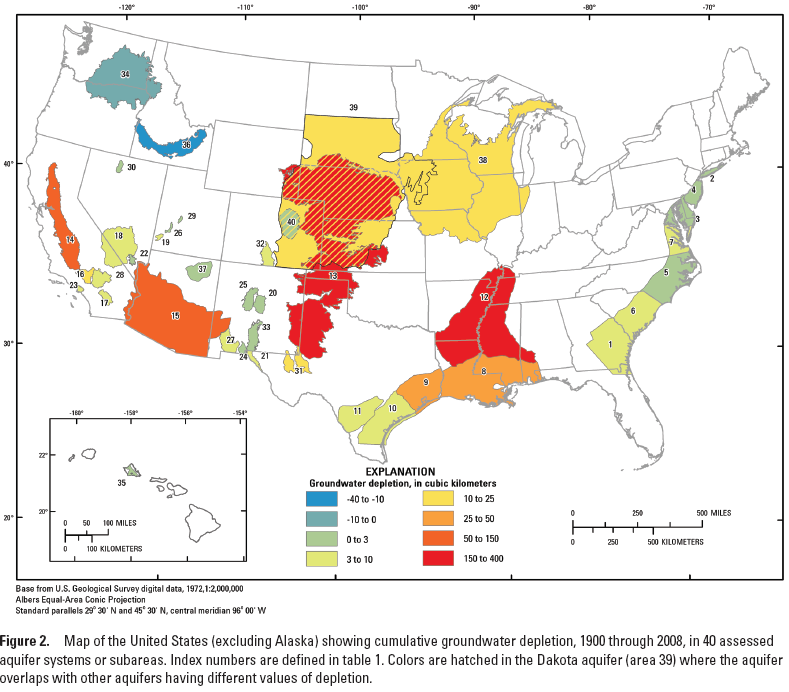

Finally, where is all this water coming from? Rain alone isn't enough, it comes from the ground. Fresh water from the ground is not unlimited, and we are running out of it. It's called Fossil Water, and here is what the situation looks like in the US:

Water withdrawals in the US

In other words, a huge chunk of our country is relying on water that will not exist in a few decades.

And looking at China:

In the US, the scale of groundwater depletion tops out around 400 cubic kilometers. In china, it tops out at 3,000 in regions. That's not to say that the US won't run out. It just says that China is in serious trouble.

Again, 80% of water use is for electricity and agriculture. And China has 4x the people of the US. There is not sufficient water. Would you rather run out of electricity, or run out of food? It's not an easy choice, but food can be imported. That being said, someone has to grow the food, and that country better have a robust water supply. Moreover, food growth is a low income industry. A country that marries itself to being a food supplier, unless it charges gouging levels of prices, is marrying itself to never being a high-income country. But charging price-gouging levels is a bad idea.

While this mental exercise was fun, let's look at some examples.

First, while Californians probably shouldn't have been growing water-intensive almonds in a dessert in the first place, running out of water has imperilled the world supply of all sorts of nuts and things. They are tearing up their farms because of lack of water.

That's only the start. Drought in Syria helped bring about war there. Syria is a tiny country that doesn't matter on the world scheme. India, China, and Pakistan face water shortages. Combined, they have 1/3 the world population. They also happen to hate each other. As climate change progresses, and some countries face droughts, people may not want to choose between food and electricity. They may try to divert water supplies, sparking tensions and even war.

So. Does your power plant have a drinking problem? If you live in China, it definitely does, and it's causing all sorts of strife.

Wrapping it all together: Yes, a country can import food. But you know how much of the world relies on the middle east for oil, and we talk about energy security? That's just stuff that makes your cars move. Remember how Russia threatens to shut off natural gas to Europe if they don't get in line with Russia's plans, and so much of Europe is cowed? That stuff keeps homes warm, but it isn't as important as food. Imagine a powerful country that is mostly reliant on other countries for food to stay alive. That's a really bad situation. The country in this situation has to either take dictations from whoever feeds them (not really a problem if you are getting your food from non-powerful nations, but still irksome), or has to take over a food-producing country.

One potential solution: Chinese power plants are notoriously inefficient. If you have a 25% thermodynamically efficient powerplant, it uses 30% more water than a 37.5% efficient power plant. China should either shut down inefficient plants and require new construction that is efficient, or require retrofits of old plants. It would be very expensive, but less expensive than the social and political cost of running out of water too soon. What about the US? Most of our plants are pretty efficient already. Especially our Natural Gas plants that much of the country runs on. We probably spend too much water on watering desserts to make food, but that's another story.

An almost-final note. While solar power and wind power use water in construction, their water use is minimal compared to that of thermal power plants. Barring solar-thermal (it's thermal, it uses water), these renewable resources are the only answer to the reducing the choice between electricity and food. In other words, expansion of wind power and solar PV is the only cheat code we have to deal with this impending water shortage.

One last thing. Why did I single out China? Only because I know a lot about China. Pakistan will have water shortage issues, but they already don't have electricity. In the summer, they have blackouts for up to 20 hours a day cause they can't produce enough electricity. This is a country of 180 million people, bordering India, and sharing a strong mutual resentment with India. More on this later, though.

Thanks for reading,

- Jason Munster